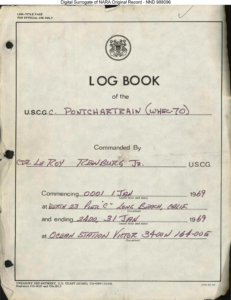

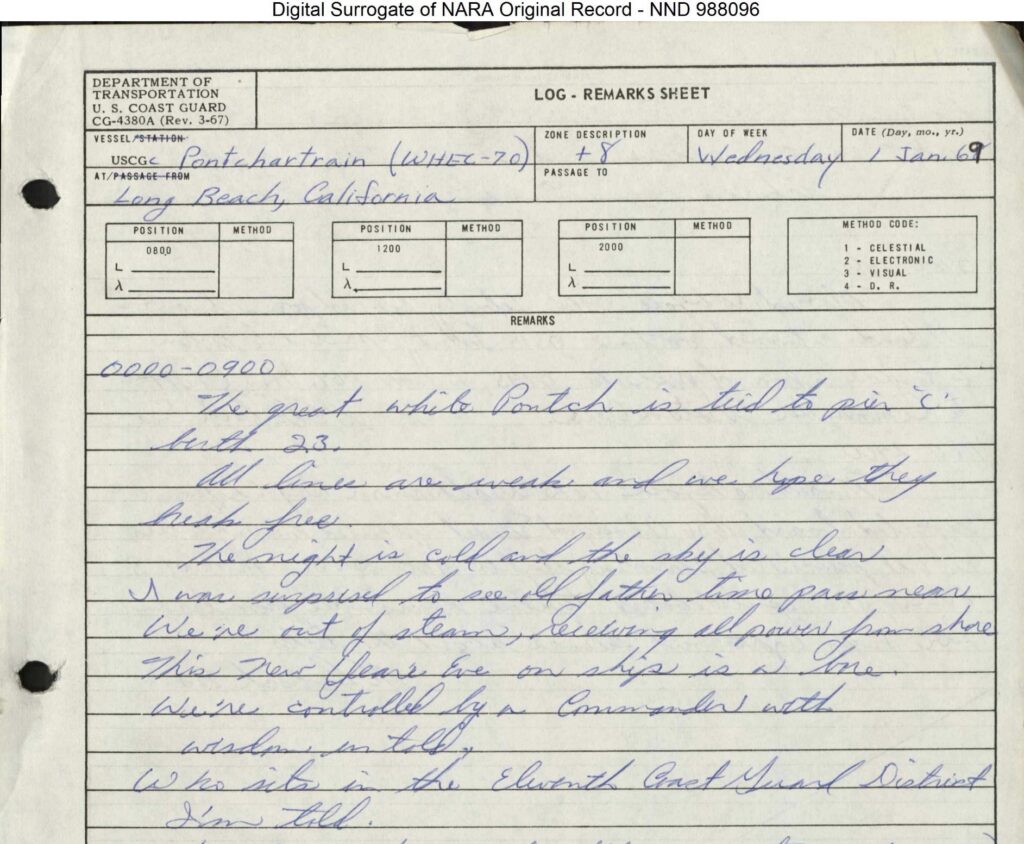

During most of 1970, the Coast Guard Cutter PONTCHARTRAIN (WHEC-70), of which I was the commanding officer, was deployed to Vietnam as a unit of Coast Guard Squadron THREE, a part of Commander, Cruiser/Destroyer Group, U.S. SEVENTH Fleet.

U.S. Coast Guard cutter PONTCHARTRAIN Squadron Three insignia, Vietnam, 1970. Photo by LeRoy Reinburg, Jr.

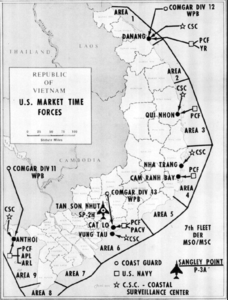

PONTCHARTRAIN was a 255-foot, single-screw high endurance cutter, with a steam driven, turbo-electric propulsion system, with a wartime complement of 230 enlisted personnel and 25 officers. When we were operating off the coast of the Republic of Vietnam, we were under the operational control of the Commander, U.S. Naval Offshore Patrol Force (CTF 115), code named MARKET TIME, tasked with interdicting North Vietnamese trawlers and other craft which were constantly attempting to pierce the barrier patrol and resupply the Viet Cong with personnel, ammunition, and other supplies. In addition, we provided Naval Gunfire Support (NGF) to friendly forces ashore with our five-inch, 38-caliber general-purpose gun. We were also armed with 20mm machine guns on each bridge wing, a quad 40mm machine gun mounted forward of the bridge, and six deck-mounted 50-caliber machine guns. Just prior to our departure from Long Beach, California, our home port, we were directed to remove our sonar, and Antisubmarine Warfare acoustic torpedoes. As I will explain later, we regretted the loss of the sonar.

Republic of Vietnam Navy patrol boat alongside U.S. Coast Guard cutter Pontchartrain, Vietnam, 1970. Photo by LeRoy Reinburg, Jr.

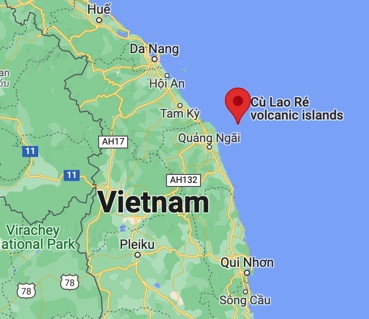

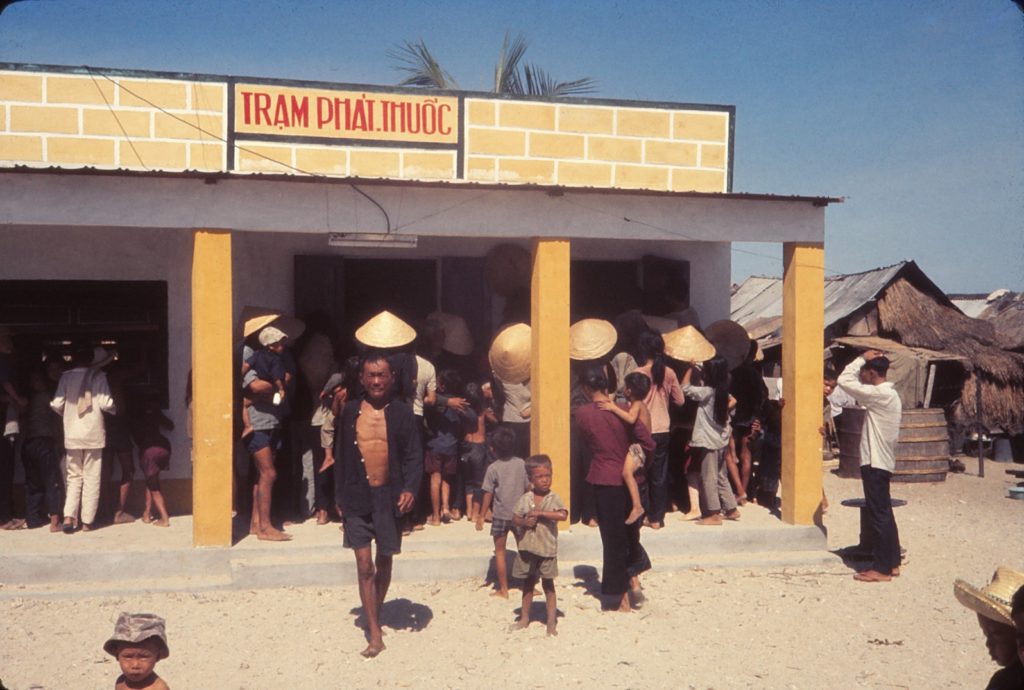

The waters adjacent to the Republic of Vietnam were divided into nine patrol areas, with Market Time Area One bordering the Demilitarized Zone and Area Nine from the southern tip of the Ca Mau Peninsula to the Cambodian Border. This latter area covered a substantial portion of the Gulf of Thailand. Each of these areas extended out to 12 miles from the shore. We boarded dozens of junks looking for contraband and draft dodgers, answered numerous calls for fire, and provided MEDCAPS (medical treatment) to the villagers. Our patrols in Areas One through Eight do not bring forth any memorable incidents, except for us watching a constant stream of Russian cargo ships steaming north to Hanoi Harbor with deck loads of tanks and trucks, and returning with empty decks. According to seagoing practice, we exchanged flashing light signals with ships we encountered in international waters, which almost always returned our queries with their name, port of origin, and port of destination. After establishing contact, we would frequently exchange pleasantries. The Russian ships, however, never answered our signals. Although we had frequent calls for fire in these areas, it was Area Nine where much of our action took place.

U.S. Coast Guard cutter PONTCHARTRAIN receiving 5-inch powder cases, UNREP (Rearm), Vietnam, 1970. Photo by LeRoy Reinburg, Jr.

In Area Nine, there had been very few attempts by North Vietnamese infiltrators. We would patrol on a random basis, and then usually, anchor at night about 500 yards off of Song Ong Doc, the site of a U.S. Navy Riverine Force Base, and provide Naval Gun Fire Support. The base was on “ammie” barges, which were moored to the shore and provided a dock for Swift Boats and PBRs to moor, and galvanized iron structures, containing an operations center and berthing space for the off-duty boat crews. The ammie barges were heavily sandbagged, with machine gun emplacements, and the base was ringed at a distance of about several hundred yards by acoustic, magnetic, and seismic sensors, precisely charted to alert the base of any attempt to overrun it. The base had armed helicopter support available to it from a nearby U.S. Army unit, but their best defense was our five-inch gun. At night, Viet Cong would try to attack the base, and we would receive frequent calls for fire on a specific sensor activation. Some nights there would be no action, then we would get three or more calls. When we received these calls we would sound general quarters, condition II, a modified version of general quarters for shore bombardment (SHOBA), in which only the gun crew, combat information center, fire control, and ship control would report to their battle stations. A strictly formatted call for fire message would include a target description, specific coordinates, and type of ammunition requested, typically HECVT (high explosive proximity fuse, set to explode above the target.)

A break after a firing mission aboard U.S. Coast Guard cutter PONTCHARTRAIN, off the coast of Vietnam, 1970. Photo by LeRoy Reinburg, Jr.

The first few times we answered a call for fire, we were not very fast, but after we had done it a number of times, we got progressively better. Eventually, from the sounding of the general alarm, Condition II, we had rounds in the air in four minutes! This was pretty astonishing, considering personnel woke up to the alarm, and raced to their stations, acquired the target, brought ammunition to the mount, reported manned and ready, and answered the “battery released” order. All during my tour, it was apparent that most of the action at sea and ashore took place at night. We had many sleepless nights, and I made sure that during the day, we had periods during which all hands were able to stand down, rather than push ourselves to exhaustion.

Anchoring close to shore at night had its own hazards. The enemy made frequent attempts to penetrate our defenses with swimmer sappers, who tried to attach limpet mines to the side of the ship. This was when I regretted the loss of our sonar. It was

CDR LeRoy Reinburg, Jr., U.S. Coast Guard. Commanding Officer of USCGC Pontchartrain (WHEC-70), Vietnam, July 1970.

a very effective method of discouraging swimmers, since the noise of the sonar signal was a powerful deterrent to approaching swimmers. We found it necessary to slide a collar up and down the anchor chain all night at periodic intervals, have armed personnel roaming the decks, shooting at anything in the water, and at random intervals detonate concussion grenades alongside of the ship. The entrance to the river off which we anchored was full of floating coconuts, which at night resembled a swimmer’s head. The rattle of gunfire and the detonating of grenades made it difficult to get to sleep. It was like trying to sleep inside a bass drum.

After weeks of this routine, it was inevitable that the deck guards would fall into a routine and become less vigilant. One night, we heard a deafening explosion to the north of us, and monitoring the fleet broadcast, found that a Navy LST moored off another Riverine Base, had a limpet mine blow a hole in the engine spaces, killing several sailors, and causing severe flooding. This was a heads up for all hands, who got the message that we might be next. It wasn’t necessary from then on to make them aware that perpetual vigilance was essential.

Deck litter during naval gunfire support mission, USCGC PONTCHARTRAIN, Vietnam, 1970. Photo by LeRoy Reinburg, Jr.

While we were at anchor off Song Ong Doc, we had frequent visits from Navy Swift Boats, PBRs, and Coast Guard 82-foot patrol boats, wanting water, fuel, materiel repair support, and just a change of venue to a more stable platform for a few hours. The CO of the Riverine Base, a Navy Lieutenant Commander, would come out from ashore to confer on operations and discuss how we could improve executing our mission. I, in turn, would go ashore to visit the Base with the ship’s operations officer and gunnery officer so that we could understand each other’s strengths and limitations.

A detachment of Navy Seals operated in the area of the Base, conducting clandestine (Black) operations against the enemy. On their many visits to the PONTCHARTRAIN, I engaged a number of them in conversations and heard some of the most fascinating tales I had ever heard. I’ve listened to enough sea stories to be able to detect embellishment or tall tales, but these tales were recounted in such a matter-of-fact, candid, and sincere manner, I was sure they were, if anything, understated. One told me that on one recent occasion, he and his fellow Seals made one of their regular forays into the local jungle to harass, collect intelligence, and disorient the Viet Cong, who were constantly attempting to overrun local ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) and U.S. military bases. They stole up behind a small group sitting around a tiny campfire, silently capturing two of them before the others realized what was happening. As the other Viet Cong in the group came out of their daze from the suddenness of the attack, they abandoned their weapons, fled to the bank of the nearby river, and seemingly disappeared. After the Seals reconnoitered the area, they noticed two reeds in the shallow water near the bank of the river that seemed different from the surrounding growth and concluded that the missing enemy was breathing through them while they were submerged. Slowly the Seals crept up on the reeds, snatched them from the water and waited until the VC could hold their breaths no longer, and burst to the surface, at which that time, the Seals captured the VC. After hearing this story, I understood the degree of stress these sailors lived with day in and day out.

Because of this and other like stories involving even more intense enemy contact, I was not surprised when the Seals would ask us if they could spend a weekend of R&R on our ship! After all, we had a safe, air-conditioned space for them to sleep, hot showers, three hot meals a day, medical treatment (we had a doctor on board), and a ship’s exchange for them to buy soft drinks, “pogie bait,” and health and comfort items. After the crew of my ship had a chance to talk to these tough, combat-wise heroes and appreciate the severe stress and primitive conditions they lived under every day, I never heard any member of our crew complaining about their working and living conditions. I think it was a sobering message to all of us that we had a pretty good deal compared to our brothers in arms ashore.

Shrapnel holes in roof of U.S. Navy Riverine Force Base, Song Ong Doc, Vietnam, 1970, caused by U.S. Coast Guard cutter Sherman firing on friendlies, 1970.

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 45 No. 6, January 2006, The Military Order of the World Wars.)

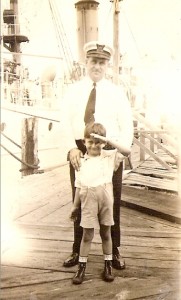

On Navy Day, 1928, my father, a U.S. Coast Guard commander, took my older sister and me to the Washington Navy Yard to hear President Calvin Coolidge give an address to Navy dignitaries and guests. As we passed through the gate, a tall, broad-shouldered man in uniform saluted my father and motioned us through the gate. I was very impressed with this important-looking person and asked my father who he was. He said, “That’s a hard- boiled, topkick Marine.” As an afterthought, as we drove off, he started talking about his father, who was born in 1847 and joined the U.S. Marine Corps shortly before the Civil War. Although my memory is a little hazy about the conversation (I was only six years old), I do remember that he said his father had received a commission in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. I don’t remember what the President spoke about that day at the Navy Yard, but I do remember that he spoke from one of the upper decks of what I thought at the time was a very large, gray Navy ship, to a crowd of people, most of whom were in uniform, seated, or standing on the dock.

On Navy Day, 1928, my father, a U.S. Coast Guard commander, took my older sister and me to the Washington Navy Yard to hear President Calvin Coolidge give an address to Navy dignitaries and guests. As we passed through the gate, a tall, broad-shouldered man in uniform saluted my father and motioned us through the gate. I was very impressed with this important-looking person and asked my father who he was. He said, “That’s a hard- boiled, topkick Marine.” As an afterthought, as we drove off, he started talking about his father, who was born in 1847 and joined the U.S. Marine Corps shortly before the Civil War. Although my memory is a little hazy about the conversation (I was only six years old), I do remember that he said his father had received a commission in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. I don’t remember what the President spoke about that day at the Navy Yard, but I do remember that he spoke from one of the upper decks of what I thought at the time was a very large, gray Navy ship, to a crowd of people, most of whom were in uniform, seated, or standing on the dock.