In July of 1946, World War II had been over since the previous August with the dropping of the 2nd Atomic Bomb in history on Nagasaki, Japan. Regardless of how you view those two bombings (that is, Hiroshima and Nagasaki), it brought a terribly destructive war to an end. The U.S. was assembling the largest military force in history for the invasion of Japan. Forces were being moved from the European Theater of Operations (ETO), to the Far East in preparation for what was thought to be the final and most destructive battle of WWII. The Joint Chiefs of Staff estimated that we would suffer as many as 750,000 casualties, with unknown, but perhaps even larger numbers of casualties among the enemy, since they would be defending their homeland. The free world gave a collective sigh of relief when Japan agreed to an unconditional surrender. In the years since, I have spoken to many veterans who were being transported fresh from the battlefields in Europe to the Western Pacific to participate in the invasion. I have yet to find one of these who did not say that the Atomic Bombs saved hundreds of thousands of lives on both sides. Rumors were flying around the Coast Guard Academy that if Japan were invaded, my Class of 1948 would be graduated early to participate in the war effort. Obviously this did not happen.

The Atlantic, a 185-foot schooner, under sail in Long Island Sound in 1929. Photo from Mystic Seaport Museum.

After the war, things gradually returned to normal. A large number of my class of about 175 resigned as soon as the war ended. Within a year, we had less than 100 left. Over the next two years, as the rush to get out of the service continued, we eventually graduated 62! But in 1946, activities such as the Bermuda Sailing Races were restarted. This annual event had been discontinued when hostilities commenced. Ocean-going sailing craft flocked to register for the races in 1946. The Coast Guard Academy, which had been given the 173-foot topsail schooner ATLANTIC by its owner, Mr. Lambert, was entered into the race. The ATLANTIC, which still held the record for crossing the Atlantic under sail, was the fastest sailing ship of its size in the world. When the race reinstitution was announced, for the first time a category of large, unlimited size sailing ships was included. The ATLANTIC was a natural for the competition. It had been undergoing a revamp of its entire top hamper and was being converted from a topsail schooner to a club-footed staysail-rigged schooner. The three wooden masts were being replaced by steel masts. The old hoop and grommet rig for hoisting the sails was replaced by the latest technology in ocean racing, metal tracks on the forward and after part of the masts. These tracks were designed to carry sliding fittings, which were attached to the hoist of the sails. It was truly a radical design, and one that was intended to increase the speed of the ship under sail. Every effort was made to complete the conversion in time for the race, which if I remember correctly, was scheduled to begin about the middle of July 1946. For some reason, I, a second-class cadet, was picked as a part of the crew of the ATLANTIC, along with, it seemed to me, most of the members of the football team. This cruise was designed to be a shakedown cruise for the new rig. One odd feature of the other members of the crew were a number of Coast Guard Auxiliarists, who were included as a reward for their volunteer service during the war. The Auxiliary had been started in about 1940 to allow volunteers to assist the regular Coast Guard, which always seemed to be understaffed. In theory, the idea of their inclusion was a good one, in practice, it turned out otherwise. These men were mostly middle aged, overweight, and largely incapable of the heavy physical activity required on a large sailing ship. I spoke to several of them, and they seemed to be surprised that they were expected to work; they assumed that this was a pleasure cruise.

The race was the slowest in the history of the Bermuda Races. We had light airs for days at a time, interspersed with light gusts of wind. It took us 8 days to go from Montauk Point, on the eastern tip of Long Island, to Bermuda, a distance of about 500 miles. All of us were relieved when we sighted St. David’s Head on the north coast of Bermuda. The ATLANTIC, it became obvious, did not carry enough potable water to handle a crew our size. We were on water hours the whole time. Showers could not be used. We were a smelly bunch when we anchored in Hamilton Harbor, just off the U.S. Naval Base. When liberty was granted, the first thing that everyone looked for was a shower, followed by girls, and real food, in that order.

Our stay in Bermuda was about five days of glorious beaches, girls, food, and sightseeing. Bermuda did not allow automobiles, so it was either walk or ride a horse-drawn carriage. We had a wonderful time. But when those five days ended, we pulled up our anchor and departed Hamilton Harbor, headed for “home.” We had a fine steady wind from the north, which was ideal for our trip. We were close hauled on the starboard tack, and the old girl was strutting her stuff. We logged 13 knots the first day; it looked like a short trip to New London.

Suddenly, the weather changed, the barometer started to fall rapidly, and the wind increased so that our lee scuppers were under water most of the time. It was time to shorten sail. The wind increased to thirty knots, the seas were making up. As the barometer continued to drop, the wind increased steadily. This was when we discovered that the new design had one flaw, the sails were drawing so strong that the tracks became jammed, and it was difficult to lower the sails! We finally wrestled down the fore and main staysails and the mizzen, which was a fore and aft sail, but we couldn’t budge the topmast staysails; the tracks were hopelessly jammed and eventually pulled away from the masts. As the wind increased, it became obvious that we were in for a storm. The winds went from gale force (45 knots) to gusts of 60 knots. When this happened, the sails that were still up began flapping furiously (luffing doesn’t begin to describe it). The captain told us that it appeared that we were in an early season hurricane! As the sails began to beat themselves to pieces, the seas became mountainous, and the winds reached a steady hurricane velocity. We were taking a beating. Abruptly after about 12 hours, the wind suddenly dropped to “up and down,” and the seas became confused. After about a half hour, the wind abruptly shifted 180 degrees and returned to hurricane velocity. We had gone through the eye of the hurricane.

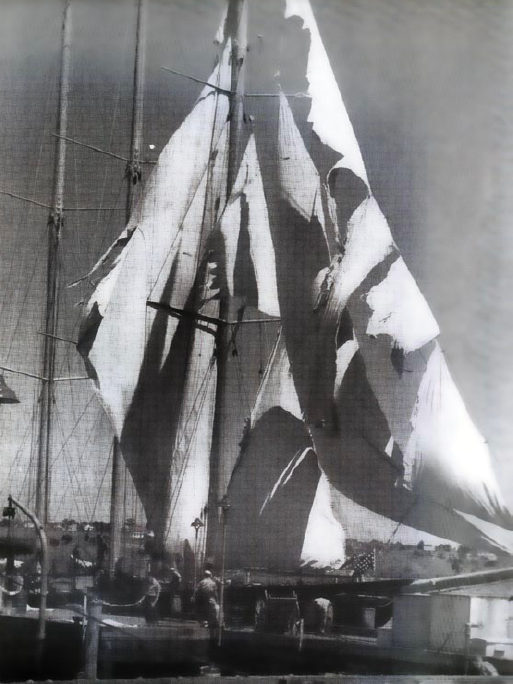

The schooner Atlantic as she appeared at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy dock after weathering a hurricane enroute from Bermuda to New London, CT, 1946.

About 12 hours later, the wind began to abate, and without any power we wallowed in the mountainous seas, with only one lonely headsail to help keep our head into the wind. Eventually, the clew of this sail pulled out of the deck bringing a heavy brass fitting with it. This slashed around like a knife and made tatters of the jib. In the teeth of the booming gale, a large merchant ship pulled up close to us and signaled (our radio went out when the winds tore away the antenna) “Do you need any assistance?” Our captain, an experienced sailor, signaled back, “We are unable to render you any assistance.” After all, we were the Coast Guard; we would never admit we needed assistance!

In the teeth of the storm, an elderly Auxiliarist appeared on deck with his glasses tied to his head, wearing a life jacket whose pockets were filled with apples and oranges. He was obviously very frightened. He didn’t seem to know that by now the storm was abating. He asked me how far we were from the nearest land. I guess he was ready to abandon ship. I said to him, “We aren’t too far.” He brightened perceptibly and said, “What direction and how far?” I pointed straight down and said, “About 1 to 2 miles.” The look on his face showed me he didn’t think that was too funny, but I do believe he thought if someone could joke about the situation, it must not be too bad.

After the storm had passed, we jury rigged pieces of sails, and after four days, we made Montauk Point. We had just enough fresh water for our steam engine to bring us into New London. We were greeted by cheering crowds. I don’t think anyone expected to see us again! Confidentially, many of us weren’t too sure we’d make it either.

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 49 No. 5, December 2009, The Military Order of the World Wars.)