When I was young, my mother used to tell me that my father (Rear Admiral LeRoy Reinburg, USCG) never talked about his World War I experiences. That’s why I was surprised that, beginning when I was about 10 years old and we were out together, he frequently spoke to me about that time in his life.

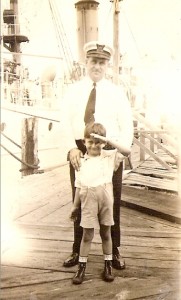

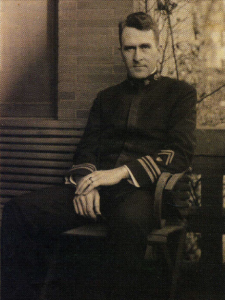

LCDR LeRoy Reinburg, USCG, shortly after his return from Europe in World War I. The two gold chevrons above his sleeve rank insignia connote 12 months in the war zone.

He had command of two ships in European waters, the first was the USS OSSIPPEE CG, which he took from Portland, Maine, its home port, to Milford Haven, Wales, which became its overseas home port. The second ship he commanded was the USS DRUID, a converted yacht on which he, the commanding officer (CO), was the only Coastguardsman. The remainder of the ship’s company was U.S. Naval personnel. He had been assigned to the DRUID by Admiral Simms, USN, the commander of all U.S. Naval Forces in the European theatre of operations. My father was an experienced CO on the OSSIPPEE, who had an executive officer (XO) whom my father had qualified for command. The Navy CO of the DRUID contracted the flu and had to be removed from the ship, but the DRUID had no qualified XO to relieve him.

The particular incident I remember my father describing to me happened when he was CO of the OSSIPPEE, a ship assigned to escort and convoy duty and antisubmarine warfare patrol. His ship was attached to a squadron of British ships under the command of a British Royal Navy Commodore. The squadron was assigned to patrol the Straits of Gibraltar to keep German submarines from transiting the Straits. Late one dark, clear, moonless night, while patrolling close to the Spanish Mediterranean shore, a lookout on the OSSIPPEE sighted several lights. As the ship closed in on the lights, hurried activity on the deck of what appeared to be a fishing vessel was observed, as cargo was transferred to an unlighted vessel alongside. Suspicious, my father, who had been called to the bridge, ordered the ship to proceed closer to the unidentified vessels. Gradually, the silhouette of the darkened vessel took the shape of a surfaced submarine. My father ordered full speed ahead and sounded general quarters, intending to ram the submarine, which by now had detected the approaching threat and was in the process of breaking away from the trawler and making a crash dive.

As the OSSIPPEE passed over the partially submerged submarine, my father said his ship shuddered as the submarine bumped along its keel. Stern and bridge rack depth charges set on 50 feet were dropped, and my father said their explosions were so violent that he thought the OSSIPPEE’s stern was blown off. All engines were stopped on the OSSIPPEE and the ASDIC listening device was monitored constantly until daybreak, but no engine noises were detected. As dawn broke, a large oil slick was observed, which was intermingled with papers, furniture, and other debris. The British Navy Commodore had been notified of the incident, and his flagship was present at daybreak, as the flotsam from the attack was clearly revealed in the bright morning sun.

According to my father’s account, the flagship moved close to the OSSIPPEE, and the Commodore, using a megaphone, called out my father’s name and said: “You’ve got him! You’ve got the Hun!” Picking up his own megaphone my father called back, “I guess that means I’ll get 500 pounds in gold,” which was the bounty the British government had placed on German submarines. The Commodore came back quickly, informing my father that this only applied to British subjects. Subsequent to this, Admiral Simms advised my father that he was to be recommended for a Navy Cross.

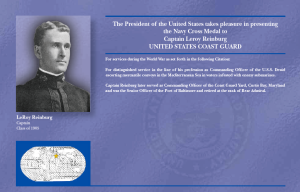

Several years after the war, when my father had still not received the medal, he contacted the Navy Department and was told that they had found evidence that he had indeed been recommended for the Navy Cross, but the citation had been lost. He was directed to prepare a new citation, which he did, and was later, in 1921, awarded this decoration. I have the original of this citation; however, for some reason, it makes no mention of the submarine-sinking episode.

LeRoy Reinburg’s citation for the Navy Cross displayed at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy’s Hall of Heroes.

Many years later, when I was a Commander in the Coast Guard and had command of my own ship, an elderly, retired Coast Guard officer, who’s name I cannot recall, came on board my ship and asked by name to see me. I was always happy to see and greet any retired Coastguardsman, but it was clear that he had a special reason to look me up, which he had done through the District Office. It seemed he had served on my father’s ship, the OSSIPPEE, during World War I, and finding that his son was on a ship close to where he retired, wanted to express his great regard for my father. In the jargon of the service, we “shot the breeze” for over an hour. During the course of this conversation, I asked him if he remembered the submarine-sinking incident. He did and gave me his very fascinating version of the event. This officer, who was the officer of the deck, called my father with the sighting and was present during the entire operation.

According to his account, as soon as it became clear that the darkened ship was a submarine, my father relieved this officer of the conn, and gave the orders to drop the stern rack depth charges, after the submarine had been “run over.” The next thing my father did was to race to the port wing of the bridge and personally release the depth charges in the bridge rack, then turn and run to the starboard wing to release those charges. The detent on this rack, however, stuck, and the charges refused to roll off the rack. My father, a powerfully built man, then jumped astride the bridge wing rail, and one by one lifted the 450-pound depth charges from their rack and threw them over the side! This incredible feat, attested to by an eyewitness, overwhelmed me. Why had my father not told me this aspect of the incident? And why, when he was asked by the Navy to write up the citation, had he made no mention of it? I have wondered about this for the last thirty years.

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 47 No. 3, October 2007, The Military Order of the World Wars.)