Editor’s note: In the aftermath of the tragic collision between a Philippine-registered container ship, ACX Crystal, and the U.S. Navy destroyer U.S.S. Fitzgerald off the coast of Japan on June 17, 2017, I recalled my father, Capt. LeRoy Reinburg, Jr. (U.S. Coast Guard-Retired), had written about collisions and near collisions involving U.S. Coast Guard vessels. This previously unpublished piece about Reinburg’s experiences in the Coast Guard sheds light on how near collisions at sea appear to be more common than many of us realize. There are no requirements to report “near misses” at sea, but personal accounts like this one contribute useful information that might add to the general discussion of ship collisions.

___________________________________________________

On many occasions in my seagoing experience, I have encountered inexcusable negligence by ship operators. As a junior officer I was attached to several vessels that manned Ocean Weather Stations. These tours were perhaps the most challenging, because most of the time on station was so routine that there was a temptation to relax your vigilance. This was particularly so when on watch as the Officer of the Deck (OOD) on the bridge, far out at sea and in good weather. According to regulations, the OOD is responsible only to the commanding officer for the safety of the ship.

Ocean Weather Stations

The United States manned a number of weather stations, starting after World War II, in support of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), to act as a plane guard for aircraft transiting the North Atlantic, North Pacific Oceans, and the Gulf of Alaska. Their additional role was to transmit weather observations, including surface and upper air observations. This was before the days of weather satellites and Global Positioning System (GPS), when areas in the center of these bodies of water were not covered by electronic navigation systems, and weather reports from ships were sparse.

The Ocean Station Vessels (OSVs) were required to maintain station in a 210-mile square and operate a radio beacon continuously, with a code indicating its location in this grid. If the ship was in the center ten-mile square, the beacon transmitted its international call sign, such as November, for the station between San Francisco and Hawaii, followed by OS (on station) in Morse code. Transiting aircraft would home on this beacon, and could have a reasonable idea of their position.

The beacon worked fine for aircraft, but ships were another matter. Most merchant ships are equipped with automatic steering mechanisms, which with a gyro compass input allow the ship to literally “steer itself.” This isn’t actually true, since the ship’s course must be manually put into the steering mechanism. After that, no helmsman is necessary for the long ocean voyages, except to change course, usually once a day, if a great circle track is followed. Unfortunately, the practice all too often results in inattention to where the ship is headed, and sometimes, there are no personnel on the bridge for long periods of time!

For the Ocean Station Vessels (OSVs), there was a double hazard. Ships would “home” on the OSV’s radio beacon while at the same time steer the ship on automatic pilot. This sometimes meant that no one was on the bridge and the ship was headed directly for the OSV’s radio beacon. The problem was much worse at night. Surface search radar on the approaching ship could easily detect a stationary target, if anyone was monitoring it. The OSV had to keep a close watch on its surface search radar to detect approaching ships to avoid a collision. If a radar (or a visual) bearing on an approaching ship is steady, that is, if it doesn’t change, collision will be unavoidable unless one or the other takes action to either change course or position.

As the OOD, I actually experienced having ships at sea home on my ship. All attempts to contact the ship were unsuccessful by voice and Morse code radio. In several occasions, we were forced to shoot off flares before taking last minute evasive action to avoid a collision. There was obviously no one on the bridge and no lookout was posted. In more than one incident, after evasive action was taken, the approaching ship sailed blithely on, completely unaware of the near collision.

Near Collision During Vietnam War Near Subic Bay

USCGC PONTCHARTRAIN (WHEC-70) in January 1970, just prior to Southeast Asia deployment.

With this rather lengthy introduction, I will recount an incident, which took place early in 1970, just west of Subic Bay in the Philippines. My ship, the USCGC PONCHARTRAIN (WHEC-70), of which I was the commanding officer, was engaged in a live firing exercise, using a surface target towed by a U.S. Navy tug. The exercise protocol for one firing run required us to steam on a parallel course with the tug at a range of 5,000 yards, about 2.5 miles, and fire our 5″-38 caliber deck gun at the target. Our fall of shot was observed and reported by the tug. This was known as a calibration exercise and was required of all ships before they departed for the Vietnam combat zone.

CDR LeRoy Reinburg, Jr., U.S. Coast Guard. Commanding Officer of USCGC Pontchartrain (WHEC-70), Vietnam, July 1970.

A Notice to Mariners was sent out about the location and time of the live-firing exercise, and my ship made an announcement on the international distress and calling frequencies to warn surface and air traffic. We also hoisted the international code flag bravo at the dip, and we prepared to commence firing. The bridge lookout reported a merchant ship approaching from astern. We tracked the ship, which would pass between the target and us! All attempts to contact the ship yielded no results. As the ship passed us at about 1,000 yards, we used our bullhorn to contact them. It was obvious that no one was on the bridge or even on deck. It was proceeding on a steady course at 14 knots. As soon as the ship was clear, we commenced firing. If the other ship heard or saw the firing, it gave no outward sign!

Dry Tortugas Near Collision

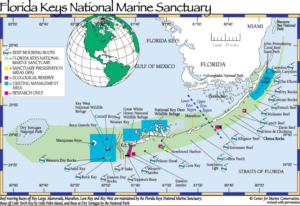

Many years later, after I had retired from the Coast Guard, I was an observer on a “drugstore tanker,” that is, a tanker that carried an array of chemicals in its ten cargo tanks. I was working as a civilian on a Coast Guard contract to assess the safety of operations of deepwater ports, which were planned off the Gulf of Mexico Coast of the U.S. We departed Baltimore with empty tanks headed for the Gulf Coast to take on more cargo to be delivered to factories in the Mid-Atlantic States. Our track took us through the Straits of Florida and one half-mile south of the Florida Keys. We were following the U.S. Coast Pilot track to a point several miles west of the Dry Tortugas, the last islands in the Florida Keys. At this point, we would change course to a northwesterly direction and head for the Gulf Coast. I had had experience with these tracks before off the West Coast. North and south bound ships all head for the same point, creating potential collision situations.

Although I had never sailed in the Florida Keys before, Dry Tortugas looked like the same hazardous situation I had encountered while on Coast Guard vessels. As we approached the turning point, a large cargo ship was overtaking us, obviously headed for the same point we were. I was on the bridge as both vessels converged. Since we were the privileged ship, that is, we had the right of way, we waited for the other ship to reduce speed, change course or take some action to avoid collision. The captain was on the bridge of our ship, observing the other ship through binoculars. As we thundered along at about 17 knots, I wondered who would win this game of “chicken.” According to the Rules of the Road, the privileged ship must maintain course and speed until “only the actions of both vessels can avoid a collision.” When I was the captain of my ships, I made sure that I never allowed myself to wait until I was in the “jaws of collision,” before taking evasive action. The captain of the tanker I was on, however, didn’t seem willing to relinquish his right of way.

As the two ships reached what I estimated were several hundred yards distance from each other, my ship blew its whistle, attempted to raise the other ship in voice radio and finally flashing light. It became obvious to me and certainly the captain of our ship that there was no one on the bridge or even on deck. I began to check out mentally where the nearest life jacket locker and lifeboat were. By this time the two ships were, I estimated, about 100 yards apart. I could see the other ship clearly without binoculars. Suddenly, some one came out of a weathertight door on the deck below the bridge. He yawned and stretched, then did a double take when he saw our ship filling his field of vision. He raced up the ladder to the bridge, and shortly thereafter, the other ship began backing full speed and dropped rapidly aft. I couldn’t detect any visible sign of anxiety on the part of our captain, but the knot in my stomach didn’t go away for quite a while. You can be sure that this incident found a prominent place in my post-voyage report!

There is no requirement of which I am aware, to report near collisions at sea, however, if I have had so many such incidents in my seagoing career, they must not be rare. Although the Rules of the Road do not recommend early evasive action to avoid collision, I have always taken this course of action. It’s easier on the digestive system.

Written October 31, 2006

Capt reinburg was the best officer I ever served under.

Ccgd14 comcen

Lem w Nash rmc

Dear Chief Nash – thank you for your comment! Were you on the Pontchartrain, sir? Dad spoke so highly of the Coast Guardsmen he served with. Thank you for your service and best wishes to you this Veterans Day.

Claire Reinburg

Interesting article concerning Rules of the Road.

I served on the USCGC Mellon and pulled several Ocean Station Victors before transferring to the Winnebago (sister to Ponchartrain). Then did a 10 month tour from 20 September 1968 to 19 July 1969 as part of Operation Market Time. You may be the vessel who relieved us at Subic Bay. ?

I was a lowly seaman on the deck force and later QM and having stood a number of watches on the bridge I find these collisions involving Navy vessels difficult to understand.

Following discharge, I worked on a committee boat for an East Coast Yacht Club which will remain nameless and witnessed several close calls between sailboat racers and large ships operating within narrow channels. These racers know all about sail shape and boat speed. Unfortunately, many have never heard of “Rules of the Road” and believe as sailboats they are the stand on vessel in situations they are required to give way.

Fair winds and calm seas,

Richard Bono

A landlocked X Coastie