During most of 1970, my ship, the Coast Guard Cutter PONTCHARTRAIN (WHEC-70), of which I was the Commanding Officer, was deployed to Vietnam as a part of the U.S. SEVENTH Fleet. We were assigned to Commander, Task Force ONE ONE FIVE, the Offshore Surveillance Force. Our mission, together with five other WHECs, Navy destroyers, destroyer escorts, and other Navy and RVN assets, was to interdict North Vietnamese trawlers, who were constantly trying to penetrate our barrier patrol and land supplies and personnel to support the Viet Cong (VC) in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). In addition, we would provide naval gunfire support (NGFS) to friendly forces ashore.

The total deployment was about ten months, and during this time we would be on combat patrol for roughly four to six weeks, with an in-port maintenance period at the U.S. Navy Base, Subic Bay, Republic of the Philippines. This schedule also provided brief, occasional rest and recreation (R&R) visits to other foreign ports, such as, Hong Kong, Singapore, Kao-Hsiung, and Bangkok. The combat patrols varied in operational intensity from relatively routine to sometimes frantic.

One of our duties required NGFS to the U.S. Navy Riverine Force Base at Song Ong Doc in the U Minh Forest area of South Vietnam. This latter duty would involve anchoring several hundred yards off the river entrance and responding to “call for fire” from the navy base, which was ringed by precisely charted magnetic, seismic, and acoustic sensors. The VC were constantly attempting to overrun the base, mainly at night. When the base received a sensor activation, they would give us a call for fire, and we would fire rounds at the sensor location. This required going to general quarters (GQ) Condition THREE, shore bombardment (SHOBA) on very short notice. Personnel would be roused in the middle of the night with the sound of the GQ pinging and would have to race to their battle stations, half asleep, and be prepared to respond to a “battery released” command. Sometimes this would occur four and five times a night, making many sleepless nights.

In addition to this, VC swimmer sappers were constantly trying to attach limpet mines to the hull of the ship, which if exploded would open a large hole in the hull. For this reason, whenever we were anchored close to shore, there were armed sentries roaming the weather decks, armed with rifles and concussion grenades. They were instructed to fire on any objects in the water, and at random intervals toss grenades in the water to discourage swimmers sappers. Since we were anchored off the river entrance, there was much flotsam streaming out of the river, particularly coconuts, which resembled a swimmer’s head.

In sum, between GQ, the rattle of gunfire, and the detonation of grenades, sound sleep was almost impossible when we were at anchor. One of the crew likened it to sleeping inside a bass drum. Being underway wasn’t much of an improvement for me, since I was called frequently to report sightings, engineering casualties, release messages, changes in maneuvering, and other occurrences in a seemingly endless array. I never complained about being called any time the officer of the deck (OOD) was in doubt. To do so might discourage him from calling me for something very important.

With this rather lengthy discourse, I wanted to “set the stage” for the main point of my article. After four or five months of this “routine,” when we arrived in Subic Bay for maintenance, I found myself very stressed out and jumpy. I had difficulty sitting still for any length of time, and even more difficulty in concentrating. I spoke to the executive officer, a wonderful, experienced, self-possessed “mustang.” This term is used to describe officers who came up through the enlisted grades. Or as, my father, an old Coast Guard hand used to say, they “came up through the hawse pipe instead of over the gangway.” I told him I had to get off the ship for a few days, and I intended to ask the Coast Guard Squadron Commander to grant me some leave while we were in port. He assured me that he could handle things during my absence. The Squadron Commander, an old time friend agreed, but said, he would give me “leave in a basket,” that is, I would file leave papers with him, and if I came back in “one piece,” he would tear them up.

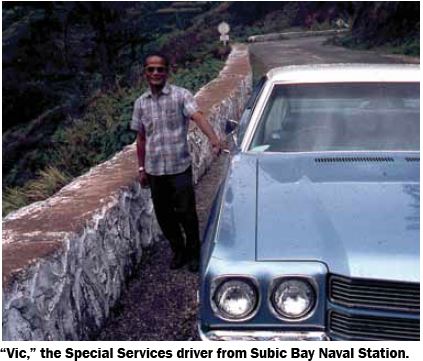

The next day, I hired a car and driver through the Navy Exchange, at the exorbitant rate of 6 US dollars per day! The exchange rate at that time was 8 pesos to the dollar, and the peso had the same purchasing power in the local economy as a dollar did in ours, so the exchange and the driver were well compensated. I packed a bag and left the next morning on what would be one of the most interesting and satisfying trips I have ever taken. My driver’s name was “Vic.” He spoke beautiful English, as is common in the Philippines, and I told him I wanted to go to Baguio, which is a mountain resort north of Manila, on the main island of Luzon. I would stay at Camp Hay, a U.S. Army Recreational Facility. I told Vic that I would like to take an interesting route and he assured me he knew of several.

The next day, I hired a car and driver through the Navy Exchange, at the exorbitant rate of 6 US dollars per day! The exchange rate at that time was 8 pesos to the dollar, and the peso had the same purchasing power in the local economy as a dollar did in ours, so the exchange and the driver were well compensated. I packed a bag and left the next morning on what would be one of the most interesting and satisfying trips I have ever taken. My driver’s name was “Vic.” He spoke beautiful English, as is common in the Philippines, and I told him I wanted to go to Baguio, which is a mountain resort north of Manila, on the main island of Luzon. I would stay at Camp Hay, a U.S. Army Recreational Facility. I told Vic that I would like to take an interesting route and he assured me he knew of several.

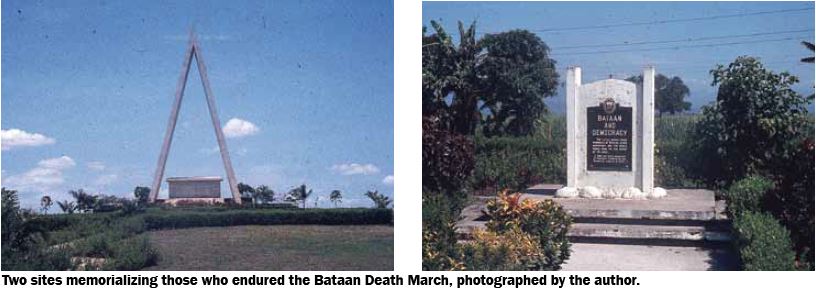

I had heard of the Bataan Death March, during the early days of World War II, and asked Vic if this was on the way to Baguio. He was somewhat hesitant, but agreed. I found out later why. We picked up the Death March route well above Marivales, where it started on April 10, 1942, after 76,000 U.S Army and Philippine Scouts surrendered to the invading Japanese Army. As we drove the route, Vic displayed a very comprehensive knowledge of the event, explaining in detail what had transpired. After WWII, the Philippine government had erected memorials along the route commemorating those who died. At one stop, as he spoke, Vic was visibly emotional. He told me in a halting voice that he was a survivor of the Death March, having escaped along the 60-mile route to Camp O’Donnell, where they were to be incarcerated. After his escape, he joined the Philippine guerillas and fought the Japanese in the jungles until the end of the war. He told of the utter brutality of the Japanese guards, who bayoneted and shot, and in some cases beheaded Americans and Filipinos who dropped by the side of the road from exhaustion on the 5 to 6 day journey, due to heat, malnutrition, and lack of water. Of the original 76,000, only 54,000 reached the prison camp!

As Vic spoke, I, too, was overcome with thoughts of the terrible ordeal and forgot about my troubles which seemed petty compared with what Vic and his fellow prisoners endured. It somehow had a cathartic effect on me, and as the trip wore on, I noticed that I was a little more calm and collected.

The remainder of the trip went by rapidly. Vic spent the nights with his family, and during the day, he chauffeured me around the lovely city of Baguio. The nights were positively chilly, after the oppressive heat of Subic Bay. We even had a fireplace in the hotel and a fire in the evening provided a comforting sight. After several days relaxing in Baguio, our trip back to Subic was uneventful and oddly had a deeply calming effect on me. On our arrival in Subic, I gave Vic a substantial tip, and I could hear the catch in his voice as he accepted it. I think I had helped him as much as he helped me, and I had made a new friend. I returned to the ship feeling refreshed and ready to get “back in battery,” as the gunnery people say.

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 49 No. 6, January/February 2010, The Military Order of the World Wars)