On June 6, 1944, the largest military invasion force in history landed on the beaches of Normandy, France, to break the hold of Nazi Germany on the European Continent. I remember this day very well. I was a third class cadet at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. The entire cadet corps was lined up in the quadrangle of Chase Hall, the cadet barracks. It was about 0630, and we were in the middle of doing calisthenics. We would normally have been rowing, but the fog on the Thames River was so thick, that it was feared that we might become disoriented and drift down stream. This had actually happened a month before, and it had taken almost a day to locate all of the pulling boats.

While we were exercising, the Commissioned Officer of the Day, came out of Chase Hall, halted the exercises, and announced in a very solemn voice that the Allied invasion of Europe had begun. He dismissed us, and we all went back to our rooms to prepare for breakfast and talk about this historic event. Many of us wondered if this would mean that the war would end before we graduated and went out to the fleet. Whatever the effect this event would have on our lives, we knew that despite the fact that the submarine war at sea raged on off our coasts, we would still depart shortly for our summer practice cruise. Our itinerary had been posted on the bulletin board, and it included stops at Miami, Havana, St. Petersburg, and New Orleans.

I think most of us were looking forward to seeing Havana, but as it turned out, the other ports were interesting as well. Our trip started with a troop train (we called it a cattle car) ride from New London, to the U.S. Marine Corps Base at Camp LeJeune, North Carolina. The trip down was miserable. The weather was miserably hot, and we were the last cars on a coal fired locomotive train. This was in the days before air conditioning. We had to open the windows because of the stifling heat, and the coal dust found its way into everything. We had about a four-hour layover in Union Station, Washington, D.C., but as I remember, it was from about 0100 to 0500, and we were not allowed to leave the train. I can’t imagine why we would have wanted to, anyway. The heat of the D.C. summer was almost unbearable.

The highlight of the trip was when we went slowly through Myrtle Beach about noon, and people lined the way waving to us, blowing kisses, and shouting words of encouragement. We spent three weeks at Camp LeJeune attending the Amphibious Warfare Training School, which involved loading combat-equipped Marines into LCVPs and LCMs (landing craft equipped with ramps on the bow) from a mockup of a transport ship, and debarking them on a sheltered beach. The beach landing, apparently, was only incidental to the Marines and our training; the debarking on cargo nets and entering the boats was the purpose of the enterprise. It was during one of these operations that I had exposure to a tragic training fatality. A Marine with full combat gear lost his grip on the cargo net and fell in between the boat and the mock transport. The water, as I recall, was quite deep, and before he could be rescued, he had drowned. I remember having tears running down my face. My boat was not directly involved, but it was a sad and sobering occurrence. Our training continued, making landings on the Atlantic Ocean beach through surf. I doubt that the purpose of our training was to make us proficient coxswains, but rather to make us aware of the problems associated with landing troops on unfriendly shores.

USCGC Cobb (WPG-181) was a United States Coast Guard cutter commissioned during World War II. The author, then-Cadet LeRoy Reinburg Jr.,

made a cadet cruise on the Cobb in the summer of 1944.

At the end of our training, we took buses to Charleston, South Carolina, and joined the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Governor Cobb, a steam-driven coastal passenger ship that had been converted to an antisubmarine and convoy escort ship. It had a helicopter flight deck, although this was the very early days of the helicopter. It also had two 5”57 caliber guns, twenty millimeter antiaircraft machine guns, called Oerlikons, due to their Swedish manufacture, depth charge tracks, and K-guns. The ship was also equipped with Sonar and all of the latest electronics gear. Since we would be transiting German submarine–infested waters, we maintained strict darken ship. Each door leading to the weather decks had a darken ship switch, and as you exited these doors, they automatically shut off the interior lights. Walking the weather decks on a dark moonless night had its own hazards, and to help avoid knee-knocking and other hazards, luminous buttons were fastened to practically everything on the weather decks. We still had a lot of head and knee knocking. Of course, there were no open lights, including matches and cigarettes allowed on the weather decks.

A conversion of the 1906 coastal steamboat

SS Governor Cobb, USCGC Cobb in the hands of the

Coast Guard became the world’s first helicopter carrier. The first flight off the cutter occurred on June 29, 1944.

We reached Miami without incident, although the ship was very hot and uncomfortable. Many of us slept on the weather decks, and suffered the risk of being stepped on during the night. Miami was visible a long way off, because it was guarded by barrage balloons on the seaward side. Our visit was pleasant, although hectic. The local citizens had planned several social functions to which they had invited young ladies to be our dance partners and companions through the evening. Since we were tied up in downtown Miami, it was easy to get to the local sights.

After this, we headed for Havana, and, as usual, arrived off Morro Castle at the Havana Harbor Entrance, at 0800. After tying up to a cargo pier in the commercial port, liberty was granted to three of the four sections. The uniform for liberty was service dress white, and three of my classmates and I went ashore. We looked somewhat out of place on the dirty cargo pier, but somehow the word of our arrival had reached the cab fleet and we were able to flag down a cab. Two of my classmates had taken Spanish and told the cab driver that we wanted to go the Hotel Nacional, even pointing to it on a commanding height above the city. We were going there because the city had arranged a dinner dance for us that evening, and we wanted to see what it was like in advance.

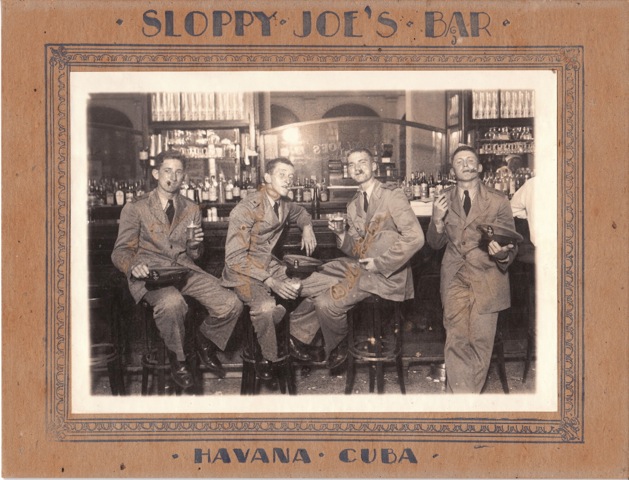

LeRoy Reinburg, Jr., (second from left) with U.S. Coast Guard Academy classmates at Sloppy Joe’s Bar in Havana, Cuba, 1944. The cadets were on a summer cruise aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Governor Cobb. From left to right, Mitton Neuman, LeRoy Reinburg, Jr., Bill Nielson, and Al Nordon. (Photo from Reinburg’s collection.)

We pulled up in front of a one story, nondescript building, and the cab driver said: “Hotel Nacional,” pointing to the building. We thought we may have made a mistake in identifying where we wanted to go, so one of us was elected to go inside to check it out. He came back saying it was a house of prostitution. After much bickering and browbeating, we finally made it to the real Hotel Nacional. The party wasn’t supposed to start for several hours, so we went back out to see some of the city. This time the cab driver took us to where we wanted to go, Sloppy Joe’s Bar, an internationally known watering place for visiting celebrities. The lesson we learned was if a cab picks up a sailor on the dock, the first thing he wants, in their view, is a prostitute.

The rest of the visit is somewhat of a blur. The party was wonderful. The young ladies were apparently from well-to-do families and had to travel with a duenna. Dating as we knew it in the States was entirely different, but we traveled in groups; some of us even got invitations to dinner with Cuban families. We traveled around the old city and had a delightful time on our own. I still have a photo of me and three of my classmates in Sloppy Joe’s. All in all it was a very pleasant and educational visit. Batista was the head of the Cuban Government, and it seemed a very happy, cosmopolitan city. Fidel Castro changed all of this in the 1950s. Now if what I read in the papers is true, everyone appears equally miserable.

Our port visit to St. Petersburg was very pleasant. I remembered it from my childhood. Here again, the citizens gave us a dinner dance, with local young ladies to socialize and dance with.

We lay off the east entrance to the Mississippi, awaiting first light to pick up a pilot for the 60 or so miles up the river to New Orleans. However, at about 0200, the sky and surrounding Gulf of Mexico was lit up by the fire from a burning oil tanker about five miles away that had been torpedoed by a German Submarine, so we immediately sought the shelter of the river, rather than being a sitting duck. We transited the river to New Orleans and arrived at a cargo pier at first light. The only incident I remember here was the accidental discharge of a forty-five-caliber pistol by the relieving officer of the deck inside the warehouse on the pier, which made a hole in the corrugated iron roof, and scared the hell out of everybody.

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 49 No. 3, October 2009, The Military Order of the World Wars.)