In the summer of 1970, I was the Commanding Officer of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Pontchartrain (WHEC-70), a unit of Coast Guard Squadron Three, Cruiser-Destroyer Group, U.S. Seventh Fleet. We were deployed to the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) and assigned to CTF 115, the Commander, Offshore Patrol Force. Our function was to interdict North Vietnamese trawlers, which were constantly trying to “run” our barrier patrol to supply arms, ammunition, and personnel to the Viet Cong, ashore in RVN. In addition, we provided Naval Gunfire Support (NGF) to friendly forces ashore.

During periods of low operational intensity, we were encouraged to provide routine medical assistance to civilian populations ashore, since we carried a U.S. Public Health Service medical doctor. These operations were known as MEDCAPs (Medical Civil Actions Programs). Most of the combat operations ashore seemed to be at night, so our daylight hours were not very active, and it was during these times that we held MEDCAPs. The shoreline of Vietnam was dotted with small villages, and it wasn’t difficult to find one convenient to our operating area.

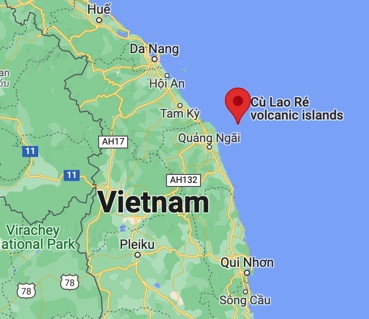

One of these villages was located on Cu Lao Re, a small volcanic island several miles off the coast, about fifty miles south of the large port of Da Nang. We anchored about a half a mile off the west side of the island and sent our small boat ashore with our RVN Navy interpreter to announce our intentions. He returned to say that the village chief was delighted to have our medical team come ashore and would pass the word among the villagers. Shortly thereafter, the doctor, the hospital corpsman, and several assistants departed by small boat with medical supplies. By this time, curious villagers were gathered on the beach. I decided to go ashore and witness the operation.

As the boat I was on approached the beach, we grounded about 50 yards from the shore, and I could see that I would have a long, wet trip to the beach. I didn’t anticipate that the villagers would send a “basket boat” to carry me to the beach. Basket boats at that time were everywhere. I had seen them launched by fishing boats to tend nets and to provide transportation from boat to shore. I had never seen one close aboard until I stepped carefully into this one, expecting that it would be very unstable. Surprisingly, it was not. It was round and about 10 feet in diameter, made of what appeared to be reeds woven like a typical basket, and covered with hard black pitch or resin to make it waterproof. Propulsion was by paddles, deftly handled by young men who were able rowers. The draft, even with several passengers, was only a few inches, and I stepped ashore without getting my feet wet. I was greeted by a crowd of small children, who stared and smiled and chattered among themselves. They surrounded me and accompanied me to the village.

I had seen villages in remote sections of Alaska and in the Philippines; however, I was not prepared for the simplicity and sanitation challenges of this one. People lived in thatched huts, interspersed with some small cinder-block structures with corrugated iron roofs, and large black flies were everywhere. I remember walking into the village square, which had a large flat pottery bowl in its center. The bowl had a mound in the center, which on closer inspection was composed of fermenting fish on a bed of large salt crystals. Between the mound and the rim of the bowl was a ring of dark brown liquid, which I found out later was soy sauce. Flies were crawling all over the mound and buzzing around it. The smell was overwhelming. As I stood looking at it, several villagers stopped, and taking small corked bottles from their belts, filled them by dipping them into the liquid. After they filled them, they took a long-handled dipper hanging on a nearby hook, dipped it into the liquid and poured it over the mound, no doubt to increase the flow of the fermented fish fluid. No one seemed to mind the flies, even though many, mostly the children, would have flies crawling on their faces. They never seemed to brush them off. I had smeared my exposed skin with bug repellent, but the flies still buzzed annoyingly around my head. I was told later that the “sauce” the people were dipping was called “nuoc mam,” a dietary staple, and everyone doused their food liberally with it.

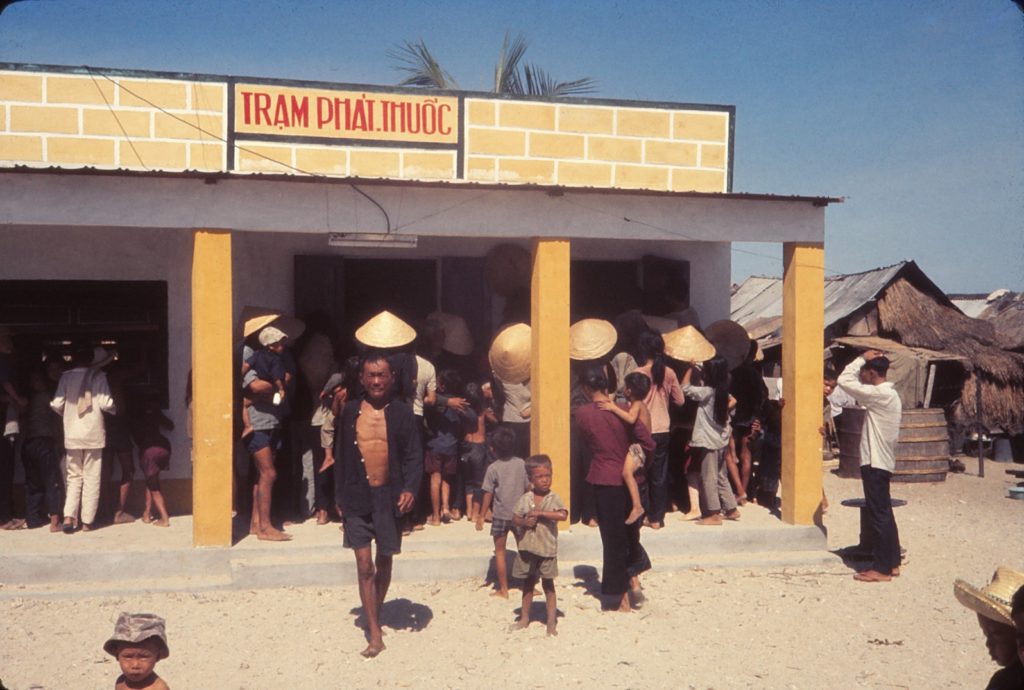

I finally found a fairly large cinder-block structure, which looked as if it was a village store. There was a covered porch on the building, and villagers were lined up outside where the doctor and corpsman were providing medical care. Some of the villagers had their arms in slings; others had crude, dirty bandages on their bodies. One little girl, who appeared to be about five years old, had one of her eyes bright red and swollen shut. I talked to the doctor later about his experience, and he told me that most of the problems he treated were due to lack of cleanliness and sanitation and poor health practices. He gave a shot of penicillin to the little girl with the red eye, but he felt badly that he would never see her again for a follow-up.

After I returned to the ship, I reflected on the challenges many people in the world continue to face without access to basic sanitation and safe living conditions. Even though most people we saw in the village were smiling and appeared to be happy, I knew we were far from meeting their basic needs through the occasional MEDCAPs mission. I was still thankful that we could at least do a little bit that day to assuage what I perceived to be their difficult living conditions.