The first thermonuclear device, called “Mike,” was detonated on a small, unnamed island in the northern part of Eniwetok Atoll, Marshall Islands, in 1952. The blast destroyed the islet and left a large underwater crater, which in 1963 was marked on the southern side by two first class cans. This was followed almost two years later by a new test program called “Operation Castle” at Bikini Atoll, the site of the first atomic bomb tests in 1946 following World War II. The first shot in this planned series was “Bravo,” a surface shot with a yield of fifteen megatons, very much more powerful than “Mike.”

The detonation occurred on March 1, 1954, at 0645, but that morning when the great volume of radioactive particles rose to 100,000 feet, instead of the upper winds depositing them harmlessly to the north as expected, they were carried to the east toward the inhabited atolls of Rongelap, Ailinginae, and Rongerik. In the area of the eastward fallout, eighty miles from Bikini, there was also a Japanese long-line 100-ton fishing vessel Fukuryu Maru No. 5 (the Lucky Dragon).

Before shot time Bikini had been evacuated, and all of the ships of the task force had been withdrawn thirty miles to the eastward. It soon became apparent that the radioactive cloud at its full height was behaving erratically. Monitoring devices on some of the ships began recording increased amounts of radioactivity. Personnel were ordered below decks, and topside openings were secured. Within a few hours, radiological safety aircraft had determined the direction, extent, and level of the fallout. The fallout pattern reached 200 miles to the eastward (well beyond the published danger area), and its southern fringe covered Rongelap and Rongerik.

Over two hundred people, including twenty-eight American military personnel, had been exposed to doses of radiation and were evacuated from Rongelap, Ailinginae, and Utirik within 48 hours after the shot. U.S. Naval ships and aircraft made the evacuation. The fallout was described at Rongelap as “snowlike” and at Ailinginae and Rongerik as “mist.”

As it turned out Rongelap received the heaviest dose, but although the population received a significant amount, there were no fatalities. The Lucky Dragon did not fare so well. It put into its homeport of Yaizu City two weeks later with its twenty-three crewmembers. They had lived for two weeks in a heavily contaminated ship and had ended their cruise disturbed and frightened by their condition. The severest cases had darkened skin, burns, and loss of hair, but this was merely the beginning of their misfortune. One of the crewmen died, and all were hospitalized with severe radiation sickness.

By December 1954, nine months after contamination, the radiation levels at Rongelap were still too high to allow the Marshallese to return. However, teams of scientists had visited the atoll three weeks after the contamination, and again three times in 1955, and from then until 1957, the Atomic Energy Commission had completely demolished all buildings on Rongelap and constructed a modern village. On June 29, 1967, all of the Rongelapese arrived back home on a U.S. Navy LST which had carried them and their belongings from Majuro, where they had been sent three years before.

In the spring of 1963, the Commandant, U.S. Coast Guard, in response to an Atomic Energy Commission request, agreed to provide a ship to support a team of scientists performing bioenvironmental resurvey of Rongelap a decade after the detonation. The tragic consequences of shot “Bravo” at Bikini assumed a more personal aspect for me when the ship selected for this task was the USCGC IRONWOOD (WAGL-297), stationed in Honolulu, Hawaii, of which I was the Commanding Officer. A date of mid-August had been tentatively set for the survey, and the Commander, 14th Coast Guard District directed that the IRONWOOD would extend its regular aids to navigation trip to the Marshall Islands to provide the necessary support

In the spring of 1963, the Commandant, U.S. Coast Guard, in response to an Atomic Energy Commission request, agreed to provide a ship to support a team of scientists performing bioenvironmental resurvey of Rongelap a decade after the detonation. The tragic consequences of shot “Bravo” at Bikini assumed a more personal aspect for me when the ship selected for this task was the USCGC IRONWOOD (WAGL-297), stationed in Honolulu, Hawaii, of which I was the Commanding Officer. A date of mid-August had been tentatively set for the survey, and the Commander, 14th Coast Guard District directed that the IRONWOOD would extend its regular aids to navigation trip to the Marshall Islands to provide the necessary support

Through correspondence with Dr. Edward E. Held, Research Professor of Radiation Biology, University of Washington (the chief scientist of the party), I learned that the expedition would commence at Eniwetok, where a temporary laboratory would be constructed on the IRONWOOD’s buoy deck. This laboratory would consist of living area for seventeen people, work benches, sinks, refrigerators, ovens, deepfreezes, and a pump and suction hoses for the collection of plankton samples.

Through correspondence with Dr. Edward E. Held, Research Professor of Radiation Biology, University of Washington (the chief scientist of the party), I learned that the expedition would commence at Eniwetok, where a temporary laboratory would be constructed on the IRONWOOD’s buoy deck. This laboratory would consist of living area for seventeen people, work benches, sinks, refrigerators, ovens, deepfreezes, and a pump and suction hoses for the collection of plankton samples.

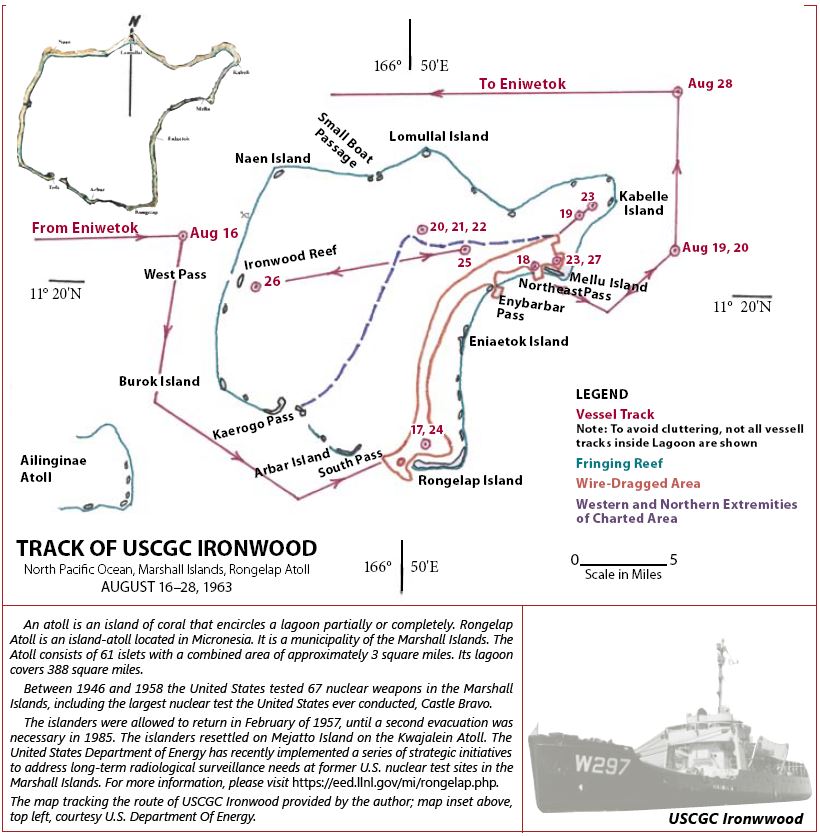

The IRONWOOD had been committed to twelve days at Rongelap, during which time, six of the major islands of the atoll would be visited, for varying periods from several hours to several days. Inspection of charts of Rongelap (U.S. Navy Oceanographic Charts 6029, 6030, and 6031) revealed that the western two thirds of the lagoon contained no data except for the location of the islands and the fringing reef. The eastern part of the lagoon, however, had been charted by the Japanese between 1917 and 1927, and showed very detailed, and as I discovered later, very accurate soundings, obstructions, and bottom composition; best of all, the whole area had been wire dragged to a depth in excess of fifteen fathoms. This was very reassuring; however, the IRONWOOD would be required to visit essentially the entire uncharted area of the lagoon, as well.

Anticipating that we might be required to feel our way around uncharted waters, I obtained two portable fathometers, which could be mounted on ship’s boats. My plan was to have a boat, or two boats, precede the ship into uncharted waters to give warning of an approaching obstruction. In June 1963, Lieutenant Commander B. L. Meaux, Commanding Officer, USCGC PLANETREE, visiting Kwajalein, and knowing of my desire for information on Rongelap, requested from the local U.S. Naval command, low-level color, aerial photographs of the lagoon. These photos were received on board upon our arrival in Kwajalein in August 1963. These photographs were excellent and gave a strong indication that the western part of the lagoon, although it had a few obstructions, was navigable.

When I first received word of our trip, I felt like Christopher Columbus embarking on his voyage of discovery, but as events unfolded, I had to admit that Columbus did not have aerial reconnaissance, radar, portable fathometers, and charts (such as they were) to remove some of the uncertainties that faced him. I believed that I had made pretty good use of the techniques available to me to reduce the risks of navigating the Rongelap lagoon, which consisted of large areas of white paper on the charts. Even the Japanese administrators of the League of Nations Mandate of the Marshall Islands had made their contribution to the success of our expedition.

On August 13, 1963, having finished all of our aids to navigation work in the Marshall Islands, we offloaded all of our buoys and appendages onto a barge at the Kwajalein Pacific Missile Range Facility to allow construction of the laboratory on the buoy deck. Due to much prefabrication and very competent work, the laboratory installation was completed the next day. After reprovisioning, we departed Kwajalein for Rongelap late on August 15.

Just after noon the next day, we entered South Pass, just to the west of Rongelap Island, the largest island in the atoll. We anchored in the wire dragged area about a mile from the village on Rongelap and established contact with the scientific party, which had flown in from Kwajalein. I went ashore to meet with Dr. Held and to meet the Trust Territory Representative and the Village Magistrate. The Magistrate told me that the villagers were eager to trade native crafts for soap, candy, cigarettes, etc., but in order not to upset the local economy, he advised bargaining. The Magistrate also asked that no one from the ship remain ashore after dark.

Liberty was granted until sunset and all hands enjoyed bartering for Tridacna (giant) clam shells, Marshallese stick charts, map cowries, other sea shells, straw fans, etc. The remainder of the day was spent (by me) meeting the rest of the scientific party, and watching them blast fish with Primacord, which we had brought from Kwajalein. The scientists cut open the stunned fish for their liver, ovaries, pancreas, and other internal organs. The flesh from the fish was given to the very appreciative villagers. The children ate the raw fish as it was handed out!

Liberty was granted until sunset and all hands enjoyed bartering for Tridacna (giant) clam shells, Marshallese stick charts, map cowries, other sea shells, straw fans, etc. The remainder of the day was spent (by me) meeting the rest of the scientific party, and watching them blast fish with Primacord, which we had brought from Kwajalein. The scientists cut open the stunned fish for their liver, ovaries, pancreas, and other internal organs. The flesh from the fish was given to the very appreciative villagers. The children ate the raw fish as it was handed out!

The scientists came out to the ship with many agricultural samples that required processing. We remained anchored overnight taking plankton samples. In the evening, at my request, Dr. Held gave a lecture to the entire crew to explain the purpose of the expedition. He explained that although there were many tragic effects of the nuclear test, it provided a scientific windfall, since there was no other known instance of single, heavy radioactive fallout on a diverse geographic area. It provided a marker to determine coral growth, examine the effect on plant growth, fish, crustaceans, and much, much more.

The scientists came out to the ship with many agricultural samples that required processing. We remained anchored overnight taking plankton samples. In the evening, at my request, Dr. Held gave a lecture to the entire crew to explain the purpose of the expedition. He explained that although there were many tragic effects of the nuclear test, it provided a scientific windfall, since there was no other known instance of single, heavy radioactive fallout on a diverse geographic area. It provided a marker to determine coral growth, examine the effect on plant growth, fish, crustaceans, and much, much more.

The next morning, the entire scientific party came on board, with all of their gear, including camping equipment. The credentials of the group were impressive. Their areas of expertise included: Invertebrate Zoology, Soils, Botany, Algology, and Geology.

The next ten days consisted of travelling into the entire lagoon, eighty percent of which was uncharted, and visiting all of the islands, taking many samples of fish, which were checked for radiation. Everywhere, Geiger Counter readings were taken and recorded. When we got underway, it was only when the sun was high in the sky to make coral reefs visible, and we were preceded by our boat equipped with a portable fathometer.

Track of U.S. Coast Guard Cutter IRONWOOD, Marshall Islands, Rongelap Atoll, August 16-28, 1963. Map drawn by Capt. LeRoy Reinburg, Jr., U.S. Coast Guard-Retired

In the course of our travels, we discovered nine uncharted islands, and one large reef that bared at low tide. Dr. Held and I decided to assign names to these geographic features. The reef, appropriately, was named “Ironwood Reef.” The Rongelapese word for small island is “bokan,” and so we named one Bokan Petrel for the smallest commissioned ship in the Coast Guard, other islands were named for Dr. Held’s wife, my wife “Bokan Marjorie,” and one of my daughters “Bokan Anora.” Because I had five children, this posed a problem in the selection, so I drew straws. All of these together with other hydrographic data we had collected were submitted to the U.S. Navy Oceanographic Office.

We departed Rongelap on August 28, 1963, for Kwajalein to have the temporary laboratory removed from our buoy deck and reclaim our aids to navigation cargo. The scientists were flown out of Rongelap by a U.S. Navy HU-16.

In the years following the March 1, 1954, nuclear accident, a high number of Marshallese have undergone surgery for cancer or potentially cancerous thyroid nodules. This has been particularly evident in those who were young children when the fallout occurred. It appears that the effects of radioactive fallout are not only slow in developing, but also a hazardous dose occurs at a much lower level of exposure than had been previously believed. Perhaps the tragedy of March 1, 1954, has further chapters to come.

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 48 No. 10, June 2009, The Military Order of the World Wars.)

Editor’s Note: For updated information on the Marshall Islands in 2015, see Washington Post reporter Dan Zak’s November 27, 2015, article A Ground Zero Forgotten: The Marshall Islands, once a U.S. nuclear test site, face oblivion again.