In February, 1970, the ship that I commanded, the Coast Guard Cutter PONTCHARTRAIN, departed from its home port of Long Beach, California, for a ten-month deployment to Vietnam to join four other High Endurance Cutters which composed Coast Guard Squadron THREE. There had been a flurry of activity prior to this, which included three weeks of refresher training at the U.S. Navy Fleet Training Group San Diego and efforts to bring on board a complete inventory of spare parts for all equipment.

USCGC PONTCHARTRAIN (WHEC-70) in January 1970, just prior to Southeast Asia deployment. From the author’s photos.

In addition, there were commissary supplies to bring on board, plus fuel and a wartime allowance of ammunition. All of these activities were time consuming and came amid the personal family arrangements everyone on board had to make to ensure their loved ones had what they needed for this long absence. My wife Marge had our six children to care for, and although she had endured my long absences when we were in Hawaii, this one was twice that long. I was apprehensive about what problems she might have to face alone. Personnel on board Coast Guard and Navy ships now have access to e-mail and ship-to-shore telephone, this was not so in those days. We weren’t completely out of touch, but communications with family, other than by mail, were difficult to arrange, except on an emergency basis.

We had two weeks between refresher training and our departure to arrange all of this, and these were hectic times, to say the least. In the middle of this “fire drill,” some one in the District Office decided to give us a new radar and a new fathometer. These were certainly worthwhile things to do to enhance our operational capability, but somehow, spare parts to keep these new pieces of equipment maintained didn’t show up prior to our departure. We were assured that they would be shipped air freight with the highest priority, and we would have them prior to our first combat patrol.

The air conditioning in the radar room failed while we were transiting the Verde Island Passage and the Sibuyan Sea (the route of the Spanish Galleons) at night with heavy ship traffic all around us. The electronics officer wanted permission to shut down the radar, which is very heat sensitive. I gave him a flat “NO!” We were in pilot waters on a dark, clear night, with many ships passing us and overtaking us. We would be unable to track any of them. We had to use the radar for the safety of the ship. At daybreak, the radar failed and we had no spare parts to fix it. The emergency was over, however, for now, and we arrived at Subic Bay that morning. When we arrived, the “priority air freight” of the radar parts had not materialized, nor had those for the fathometer. At this time we were also advised that our fathometer was so new, we were one of two ships to have it and that spare parts were not in the Navy inventory. What a great way to start our combat mission!

The time came to depart for our first combat patrol. I told the Squadron Commander (known irreverently as the Squad Dog, after his signal hoist), that the spare parts had not arrived for our radar, and this would seriously degrade our combat capability. He ruminated on this report for a few minutes, then said: “Well, Christopher Columbus didn’t have a radar.” This then was my answer, and we left the following morning. It wasn’t until well into our second three-week combat patrol off the coast of Vietnam that we received the radar parts, and we were back in business again.

Commanding Officer CDR Reinburg on the bridge of USCGC PONTCHARTRAIN off the coast of Vietnam, June 1970. From the author’s photos.

We completed our deployment of ten months without ever getting the spare parts for our fathometer, which, predictably failed after our first patrol. We were frequently operating in very shallow water for our gunfire missions, and not having a fathometer was not only irritating, but hampering to our operations. As we came into our first firing position, I asked the OOD what the depth of the water was. He replied that the fathometer was inoperative. I said: “I know that, but how deep is the water?” He told me that there wasn’t any way to determine it. Technology had come so far that he didn’t even know what a lead line was. I found to my astonishment, that the first lieutenant didn’t know either. What was even more unsettling, the chief boatswains mate, who had over twenty years service, had no idea of what I was talking about!

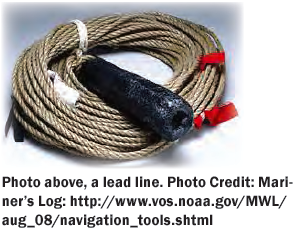

I broke out my copy of Knight’s Modern Seamanship, a standard text that I had used when I was a cadet twenty years before. I showed all of them what a leadline was, how to mark it, how to arm it (you put soap in a recess in the bottom of the lead weight, and this allows you to tell what the bottom is composed of), how to swing it, and the fact that “chains,” a small platform rigged outside the “eyes of the ship,” that is, the top deck on the bow of the ship, were needed to allow the leadsman to swing the lead clear of the ship.

After much embarrassment on the part of the first lieutenant and the chief boatswains mate, somewhere in the dark reaches of the first lieutenant’s locker (a storage location for material used by the deck force), a lead was found. I guess no one knew what it was so they were afraid to throw it away. Leadlines had been used to determine the depth of the water since probably Columbus’s time or before, but we had become so accustomed to electronic fathometers that we had forgotten all about them. After this, as we approached shoal waters, the OOD gave the order: “Man the chains!” and miraculously, we had a way to find out how deep the water was!

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 50 No. 4, November 2010, The Military Order of the World Wars.)

(Originally published in Officer Review, Vol. 50 No. 4, November 2010, The Military Order of the World Wars.)

Thanks for your comment and for sharing that information about your experience on the Pontchartrain! This account about the Pontchartrain in Vietnam by my father always exemplified for me the Coast Guardsman’s talents and remarkable ability to adapt and to get the job done in the most challenging circumstances. Thank you for your service and hope to hear more about your experiences in the Coast Guard and on the Pontchartrain.

I was one of the seaman who manned the lead line I was chosen because I was left handed